India 1995-6

Introduction

Having left our jobs - Alex as a hospital doctor and me as a producer of television commercials - to take a year’s sabbatical, we set off in late October 1995 for three months in India armed with a stack of traveller’s cheques, a Lonely Planet guide, and an optimism born of inexperience. I kept a diary throughout.

What follows is the first month of that remarkable journey, a record of its frustrations and its wonders. We were fortunate to have a comfortable budget, though not an unlimited one, and so alternated between palace hotels and rather more modest lodgings.

Reading it back now, I can hear more than a trace of Victor Meldrew. In my defence, travelling in India in 1995 was often frustrating and occasionally dumbfounding. Today, with online bookings and streamlined bureaucracy, much of the challenges has been smoothed away.

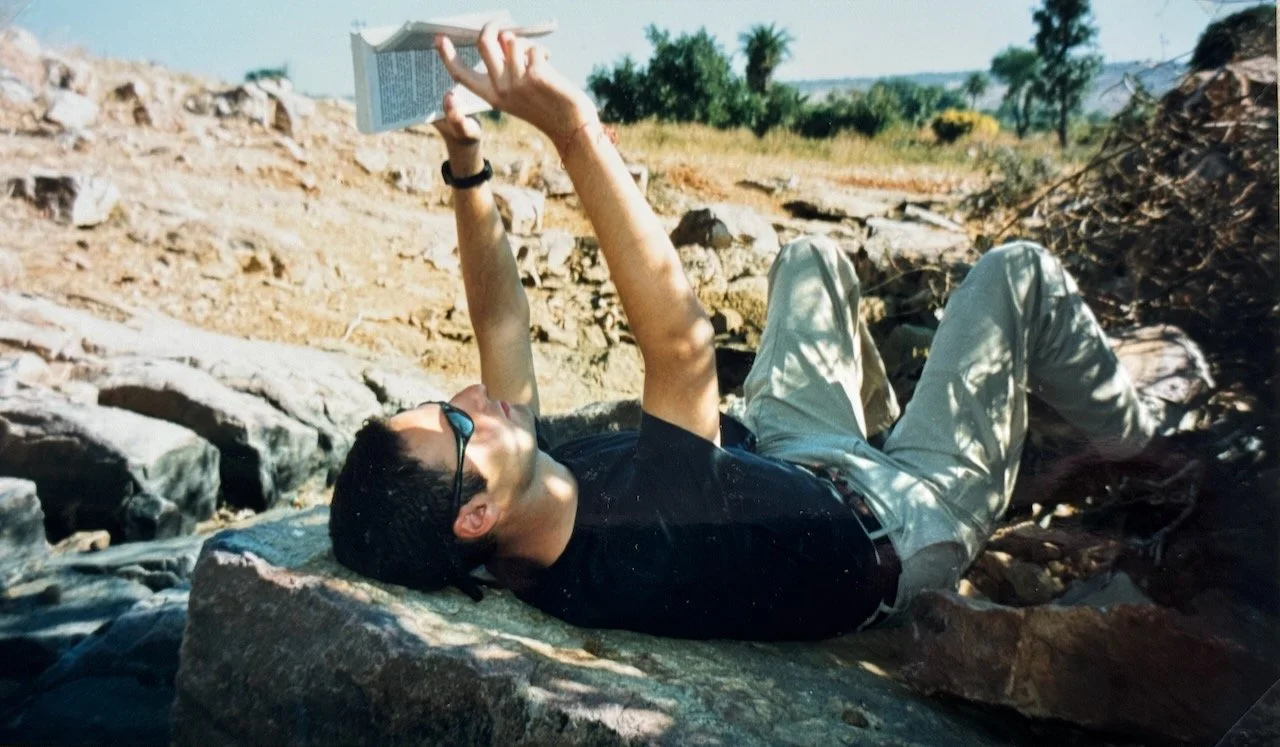

The photographs included here are from my cheap but effective Canon 500N SLR cameras, alongside Alex’s more candid shots — including one of me taking a bucket bath.

29th October 1995

Woke at 5.30 to find the storm had subsided, Alex having had one of her sleepless anxiety nights. We headed off for Leith Hill, driving over debris from the storm. Alex was so excited that she promptly drove off the road, bursting a tyre in the process of getting back on again.

Alex’s vision in her previous night’s dream — of us walking to her parents’ house with packs on our backs — almost came true. We limped to Cherry Tree Cottage at ten miles an hour.

The flights to Delhi were as grim as one might expect, but no worse. I had Nuremberg sausages with sauerkraut and mash in Frankfurt Airport — my final pork product for a while. It was the third of five meals that day, but I figured these Western delicacies should be savoured, and damn the calories.

Delhi Airport was slightly unnerving and made Terminal 2 at Heathrow look comfortable. The first queue for passport control was agonisingly slow, but I guess we’ll get used to that. I changed $200 for a doorstop of banknotes. They told me it was the right amount, and I wasn’t about to count it.

Getting out of the airport was another hurdle. The wide space of the arrival hall funnelled into a channel only one trolley wide, overflowing with clamouring friends, relatives and drivers holding up signs. Chaos.

We rammed our way through to the prepaid taxi desk and were introduced to our Ambassador, number 0214, which, horn blaring, forced its way through the other cabs — some parked in the middle of the road, others drifting along at eccentric angles.

Once out of the terminal area, the driver, hunched over the steering wheel, was determined to take us into the city at the maximum speed of fifty miles an hour. His hand moved constantly between flashing his headlights and blaring his horn, even when the lorry in front of him was first in a long line of traffic. Roundabouts operating à la Française (cars entering the roundabout have right of way) were particularly exciting. A couple of times I really did feel that death — or perhaps only maiming — was moments away.

Eventually we slowed down and the sound of the engine (lawnmower in too high a gear at the front, Lancaster bomber at the back) thankfully receded.

The Imperial Hotel, far from being a faded glory, is in the process of being refurbished, and our room, although glacial, is rather luxurious and enormous. We were in bed by 4 a.m., and I was awake, shivering, at 7.30.

Wednesday 30th October - Delhi

Room-service breakfast was good. The coffee, requested strong, was Nescafé with four spoonfuls per cup, but the toast, muffin and honey were excellent.

After a fruitless call to Samode Palace Haveli, we left to pick up our airline tickets for Shimla, leaving the sanctuary of the hotel grounds for the noise and confusion of New Delhi.

The main confusion of ours was trying to find the airline’s office. When eventually we did, it turned out to be a labyrinth of small, cramped rooms with electrical wires hanging out of the walls, hideous strip lighting, walls that hadn’t seen paint in twenty years, and a fax on the reception desk from a parts supplier saying that various components of their plane (solenoid valves?) were corroded and required immediate replacement.

Alex’s eyes were fixed on a dusty model of a small propeller aircraft. I was glad to leave the building, which looked ready to collapse at any moment. I was amazed to see that Lintas and Interpublic (large ad-agency networks) had their Delhi offices there.

We left for a rather tasty dosa at Soma Rupa, followed by a doze by the enormous pool and ten lengths. A shower and a 153-rupee beer was followed by my first autorickshaw trip — to Gaylord — where we ate tasty but eye-wateringly, nose-runningly hot curry, preceded by poppadoms and crisps (Alex having told me the latter didn’t exist in India).

I went to wash my hands on arrival and got the full treatment from the attendant: he turned on the taps, squirted liquid soap, proffered a towel, and took some money.

We walked back to the hotel. Everything was right with the world until we asked for the bill, which we were initially told was $200 for two nights. I gulped and peeled back ten $20 traveller’s cheques. The cashier then said, “…but that doesn’t include last night.” That brought the total to $380 — on top of the $400 return flight to Simla. A pricey first day in India, but at least lunch only cost £1.50.

Thursday 31st October - Delhi to Shimla

The alarm went off at 6.30 a.m. and I found a newspaper outside the room with the headline Delhi Airport Domestic Terminal Burns Down. As this was where our flight was leaving from, we were a bit concerned.

The terminal was destroyed — or, as the article put it: “The fire was declared serious at 4.20 a.m., by which time it was a raging inferno.” It seems the whole airport was closed to all flights about an hour after ours had arrived the previous night. We were lucky not to have been diverted to Kolkata.

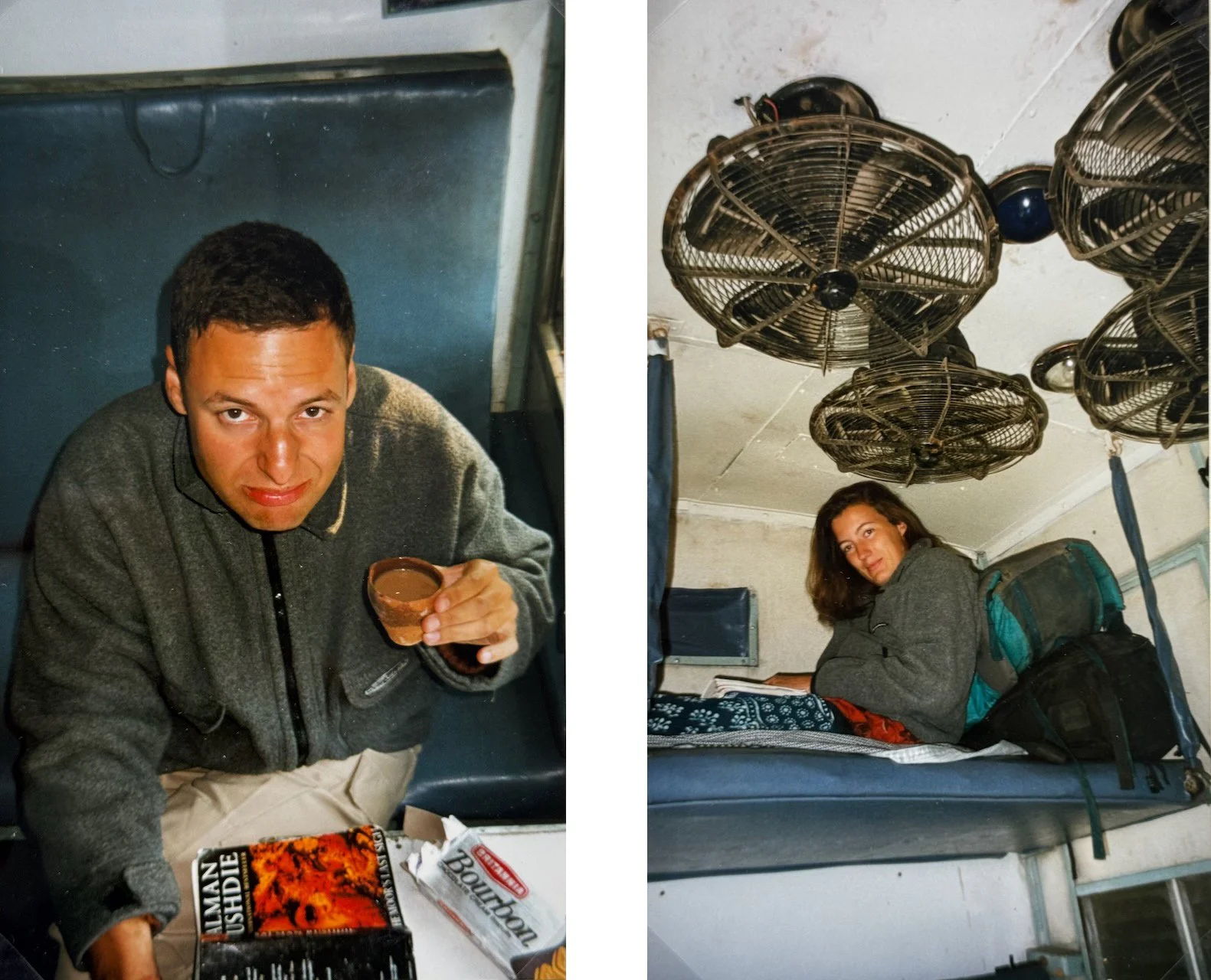

Fortunately our panic was unnecessary. Terminal 1A had burnt to the ground, while the private-airline Terminal 1B was still standing, but now dealing with all of Air India’s flights as well. We drank the usual sugary tea and coffee while we waited to check in.

Alex had the batteries confiscated from her torch — perhaps these pose some unspecified in-flight danger. I emptied the batteries from my shortwave radio. The customs officer told me they’d be returned to me on arrival in Simla, but then relented, giving me a conspiratorial wink as he dropped the batteries into my other bag.

We waited in the departure area to be told the flight was delayed thirty minutes due to bad weather. Eventually we were driven to a small propeller plane with around twelve seats, one on either side of the aisle. The cabin height was about five feet. Alex was looking pale.

In the event, the flight was very comfortable. I ate all the contents of my Jagson Airways cardboard box — at least the samosa and sandwich — and watched the plains pass by below us. After forty-five minutes, the snow-capped Himalayas were visible on the horizon as we flew over their foothills. Alex almost leapt out of her seat when the runway suddenly appeared to the left of her window. The airport, built on the top of a flattened hill, seemed to appear from nowhere.

After landing, the plane was immediately surrounded by soldiers pointing machine guns at it. Luckily they didn’t arrest me when I tried to take a photo. We were driven in a minivan on the one-hour journey to Simla along a very winding road, following lorries belching black fumes through outlying villages with their tiny roadside shops and stalls.

We passed women carrying bales of hay on their heads and small children breaking stones into pebbles and loading up plastic sacks. Once in Simla, we turned off the main road and arrived in the tranquillity of Chapslee, a huge house built in 1830 and owned by the scions the Singh family. To stay there it was required to fax the owner with a resume of our life stories as well as several reason why we might deserve to stay there; we somehow passed the test. We were greeted by Dinesh, who introduced us to the owner.

We were led to our room up some magnificent stairs enclosing a huge hall covered in paintings of maharajas, weapons, hunting trophies, etc. It looked as if nothing had been touched for at least seventy years. We were shown into our vast suite with separate dressing room and bathroom.

We were served coffee and biscuits in the courtyard by one of the many deferential and polite servants. They probably weren’t over-occupied, as we seemed to be the only guests.

A delicious vegetarian lunch followed, served on fine china by our nervous waiter: poached egg with spinach, followed by lasagne and aubergine. Pudding was fruit salad.

Outside Chapslee

After lunch, we left for a long walk around Simla — longer than expected, as Alex completely lost her bearings. We were looking for the Mall. I asked an Indian lady who just laughed. Very confusing. We backtracked, only to discover that we’d been standing on it all along.

We were searching for the Viceroy’s Lodge, which after three kilometres of walking we still couldn’t find. We did, however, make a new friend — a five-year-old boy who was telling us something unintelligible about chocolate. The town was crammed with schools and schoolchildren in myriad uniforms, all having a whale of a time running about in groups, being cheeky. Many now-ramshackle colonial buildings still stand. The Indian Army seems to have its local headquarters here. The views of the surrounding valleys are beautiful.

We returned to the hotel and sat in the drawing room for a pre-dinner beer. Our request for peanuts or cashew nuts — listed on the menu in the bedroom — caused something of a stir. Very apologetically, the waiter said they would arrive in twenty minutes. As it would have been impossible to explain to him not to bother, we let them go ahead, and we were duly served both.

Dinner was a delicious vegetarian thali served very decorously by a waiter, now in his evening uniform, which included white gloves. He stood by like a footman throughout the meal, frequently offering us more food.

We retired, extremely replete, to our beds, in which we found hot-water bottles, and immediately dropped off to sleep.

I was awakened an hour and a half later by the sound of the brass bed next to me clanging and shaking. Alex was thrashing about, muttering, “It’s too hot! It’s too hot!” Perhaps wearing leggings to bed wasn’t such a great idea.

I lay awake for three hours, eventually resorting to the World Service on my earphones and reading Kim by torchlight. The horns of the lorries woke me again for a while at six, so I felt rather spaced out at eight o’clock when our ‘bed tea’ arrived.

Friday 1st November

We ate a delicious breakfast in the garden and chatted to the owner of Chapslee, Mr Singh, whose family has owned the house since 1920. He recommended a stopping place on the way to Dharamsala.

At 10.30 we headed off in a taxi for a tour of the surrounding hills, including a stop at a zoo — mainly filled with different varieties of deer, although there were a couple of sad-looking beasts and a small café.

The drive was along terrifying roads, looping around hairpin bends with a steep drop on one side and no guardrails. Our driver, of course, beeped constantly, always just avoiding the oncoming buses. We stopped for 49 rupees’ worth of petrol — about 80p — delivered by a hand fuel pump.

After the zoo we were driven to a viewing point where three locals were waiting, each with a small telescope, hoping for some business. Unfortunately, we disappointed them and instead went for a coffee in the café on the hilltop.

The sounds of the cappuccino machine were promising, as was the foam and the sprinkling of chocolate on top, but underneath lay the usual sweet and un-coffee-like concoction.

We headed back to Simla — another white-knuckle ride — followed by another delicious thali, this time with aloo gobi, dhal, raita and bhajis.

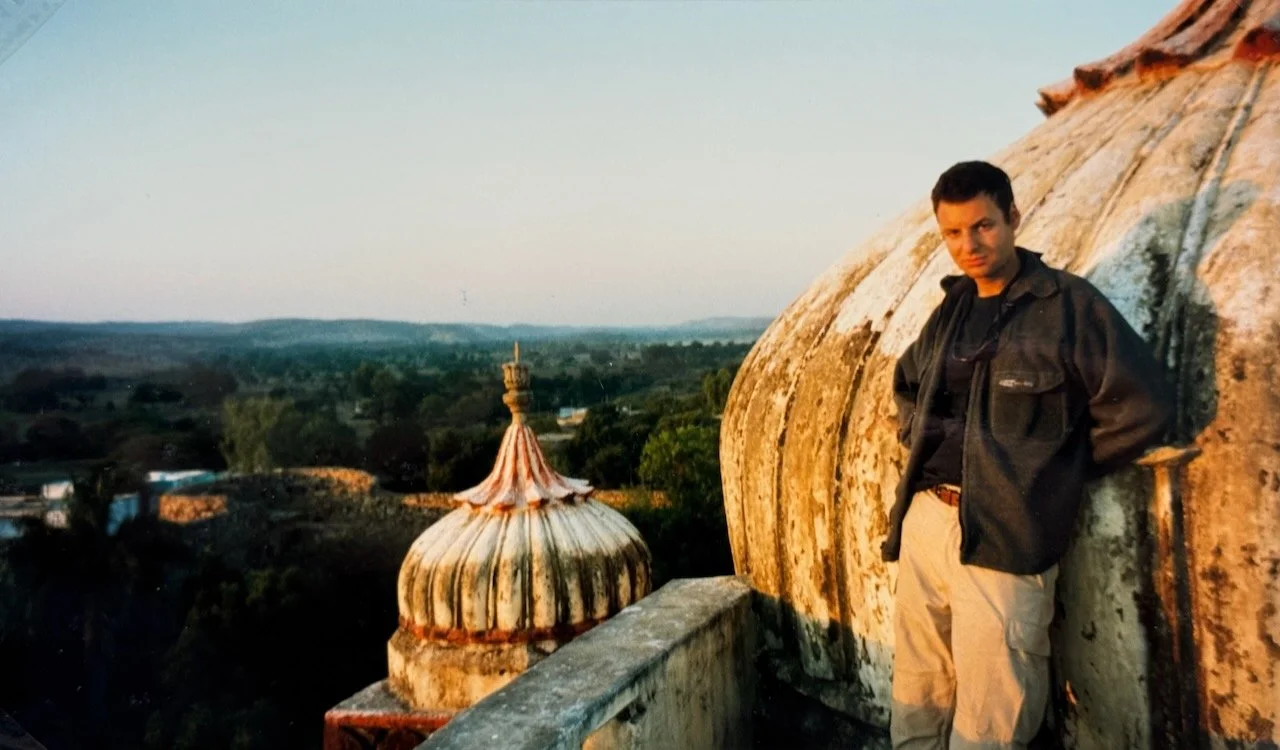

I absent-mindedly ate some of my tomato and onion salad, to Alex’s disapproval. We set off on foot to find the Viceroy’s Lodge, which we had given up on the day before. An hour and a quarter later we found it. It’s now a university building, and despite our shaking legs it was worth the walk — a huge Victorian stone structure with stunning views on three sides.

The uphill walk back was something of a nightmare, and I eyed any taxis we passed greedily. On the way back, we stopped to try to book a hotel in Dharamsala, only to discover that none of the numbers worked. Eventually we reached Chapslee, crawling up the driveway and almost climbing on all fours up the stairs.

I called the operator, who said he could only help with numbers in Simla and that there was no national directory-enquiry service.

After a shower — or mandi, as Alex prefers to call it if a bucket is involved — we were back in the sitting room nursing lagers served in silver tankards. We wisely decided not to order any nuts tonight. Yet another thali followed — so good I had to have three helpings.

Monkey sidebar

Monkeys hang out on the tin roofs when we’re trying to sleep, and then proceed to have battles that sound as if the roof is about to cave in. Alex is very scared of them; I think the baby ones are rather sweet.

Wind sidebar

I’ve been suffering somewhat, both day and night, passing about a litre an hour of noxious fumes.

Saturday, 2nd November - Shimla to Pragpur

We were woken up with bed tea, followed by breakfast outside. A uniformed servant carried a table laid with 1920s crockery: porridge (not Quaker, unfortunately), cornflakes (with hot milk, unfortunately), and toast delivered wrapped in a napkin. I had scrambled eggs to fortify myself for the long drive ahead.

Alex played with one of the many labradors and a golden retriever, which brought back memories of her own dog.

I walked up to the bank and, having filled in several forms, was finally allowed to change some traveller’s cheques. We were due to leave at 10 a.m., this time by taxi, as the bus seemed too grim. Halfway through our stressful drive, I was already wondering whether we’d made the right decision.

Our taxi was, of course, late, and we eventually set off at 11 a.m. in a small Maruti minivan. I looked at the tyres: one was new, the other three were completely bald — which went nicely with the total lack of suspension.

Three minutes into our journey there was a loud bang, which I initially thought was a firework; in fact, it was a tyre bursting. Our driver spent twenty minutes replacing it with another bald tyre before heading to a garage to fill up with petrol and fit a petrol can. For some reason this took three men fifteen minutes. By midday, we were precisely five kilometres from Simla.

The roads were terrible — full of potholes and a patchwork of bumps where old holes had been filled. The road was wide enough for one vehicle, and when a lorry or bus appeared, oncoming traffic had to drive halfway off the road and onto an even bumpier verge. During the trip, we had what felt like quite a few close calls.

We were bounced around the taxi as the mileage posts increased painfully slowly as we snaked through epic mountain passes. Having thought we would be climbing, we were in fact descending — from 7,000 to 2,000 feet — through pine forests, eucalyptus groves and apple orchards, finally reaching a fertile valley.

We stopped for lunch at 2.30 and ate our Chapslee packed lunches: a potato, a sandwich and a banana. We might have enjoyed it more had we not been parked literally on the edge of a ravine. When the driver opened the door, there was about ten inches of road and dust before a 500-foot drop to a river directly below. When I dared to leave the taxi, I clung onto the side and did my best not to look down.

We set off on the home stretch — another bone-jarring four and a half hours through valleys and villages, past schoolchildren in immaculate uniforms walking home from school. As the sun set over the hills, the taxi’s engine began to rev uncontrollably and the gearbox started banging and grinding. I had visions of sleeping in the middle of a forest for the night. Thankfully, we arrived — dusty and bewildered — at the Judge’s Court in Pragpur, another beautiful heritage hotel. We were shown to our room through a large marble bathroom and into a bedroom with a bay window, a window seat, fireplace and two large charpoy beds.

Tea and delicious sandwiches arrived. My headache, caused by breathing in the petrol fumes that had filled the taxi’s cabin, began to lift after an Alex-recommended mandi bath. We were shown to the terrace by Mr Lal, the hotel’s charming owner, and served beer and samosas with ketchup. A flautist played haunting melodies in the garden.

We were shown through to the large dining room and served vegetable dishes by nervous servants dressed in white trousers and shirts. The food arrived on a tray with three dishes. Thinking this was all there was, we filled our plates — only for a waiter to arrive with a second tray, followed by a third. All these were then offered to us for a second and third helping.

Pudding was light, delicious shortbread with homemade grape jam and peaches in syrup from the trees in the garden. The owner then recommended trying a green banana, an orange and a tangerine from his garden, which of course we agreed to out of politeness.

We went upstairs to sit in the beautiful sitting room before going out onto the roof to admire the canopy of stars shining brightly above us, before falling asleep on our very comfortable charpoys.

Sunday, 3rd November - Pragpur to McLeod Ganj

I woke up early feeling a bit peculiar — indigestion and stomach pain. I went up onto the roof to take photos of the surroundings as the sun rose. It was stunning. Eventually Alex woke up, moaning, “Turn it off, turn it off,” assuming, as usual, that any unpleasant noise must be coming from my direction — or at least from my radio. In fact, it was Hindi songs emanating from outside.

Breakfast was laid out on the lawn. Again, we were surrounded by waiting staff and had difficulty communicating our needs. I thought I’d better not refuse a curried potato croquette. As no one else was about, it was obvious they’d been prepared just for us. This was followed by toast with homemade jam.

We decided to take a walk through the gardens, full of fruit trees of all kinds, laden with enormous grapefruits, lemons and oranges. We left the garden through a gate and followed a cobbled path into the village, which looked nothing like the roadside settlements we had passed on our journey — its buildings were attractive and well kept.

I entertained the villagers with my camera as I snapped a green parrot in a cage. We then took a path out of the village, past the original gate to the estate and a walled area, about a thousand square feet, which we were later told had been the village ladies’ loo.

We passed fields being ploughed by oxen pulling wooden ploughs, for some reason tilling only a small patch of the whole field. We returned to the house via the main road, where we met Mr Lal, who was appalled that we intended to leave before lunch. Our poor driver, who slept in his taxi, wanted to drive back to Simla that night — which would have been madness even if we’d left straight after breakfast.

Mr Lal insisted that we see a little more of the house, garden and village. He showed us camphor, clove and cardamom trees, and gave us a tour — not of the house itself, but, for some reason, of the various types of plaster used to render the walls.

It seems that his family had established the village 350 years earlier for a princess. It was built in an area with no natural water supply, so the house and village have their own, piped in from a spring five kilometres away. Mr Lal explained that one story has it the village — its name created from that of the princess plus “country of” — was situated in the centre of a triangle formed by the Jwalaji Temple in Kharian, and that the prayer vibrations were propitious to the establishment of a settlement.

He then summoned a servant to show us the village, including his original family home — a beautiful building arranged around a courtyard — an enormous water-holding area, a block printer and a silversmith. We managed to avoid buying anything from the latter two.

We then left for Dharamsala, following the river valley before climbing up into the hills for yet more dangerous driving. The car seemed to have recovered somewhat since the previous day, though it still needed to be jump-started.

McLeod Ganj is made up of tiny, narrow, unmade streets with shops, restaurants and cheap hotels stacked on top of each other. The town is full of Tibetan Buddhist monks, male and female — including some Westerners — as well as civilians.

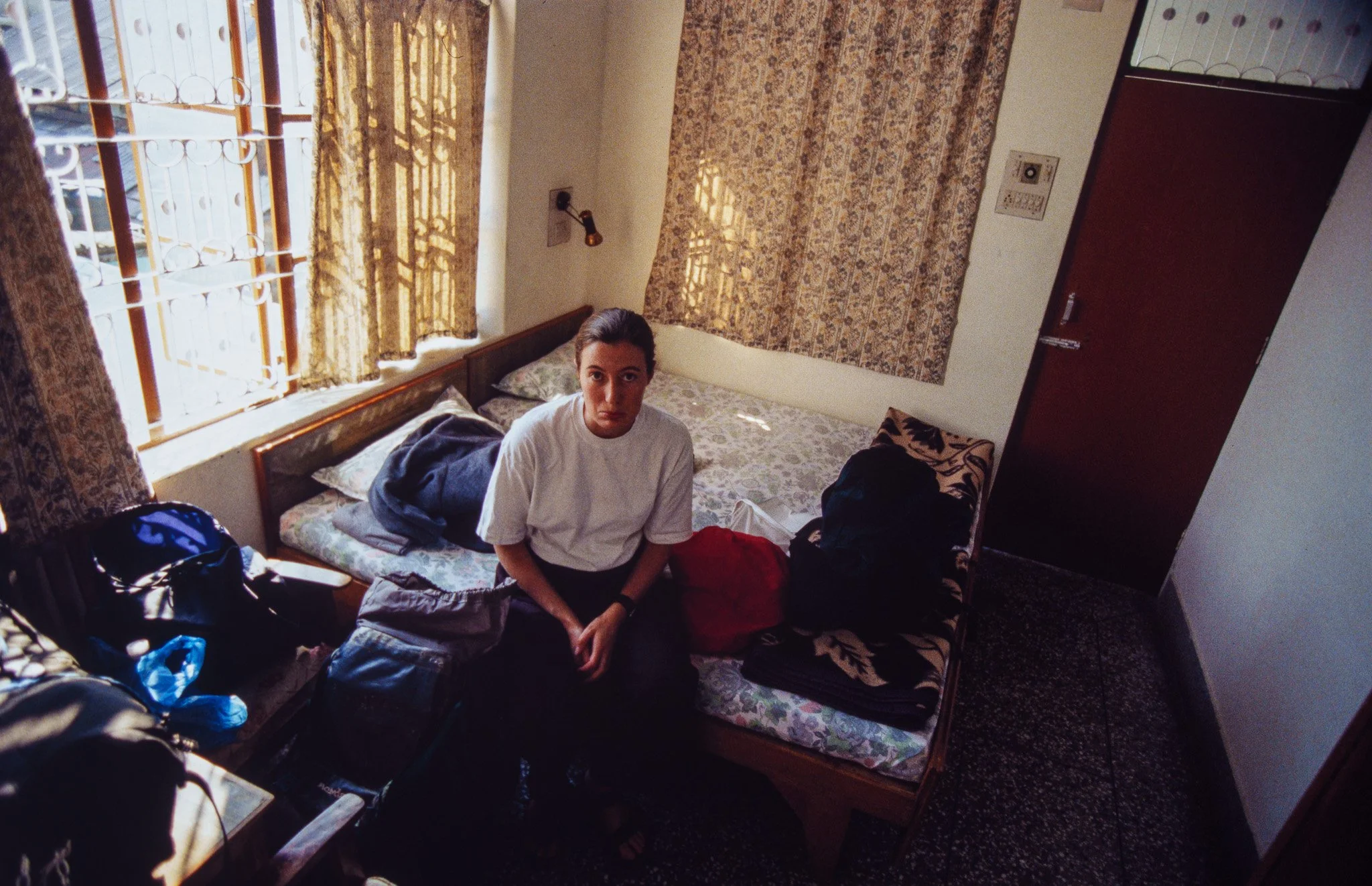

We found our hotel, which is disturbingly basic after five nights of luxury and pampering. But what more could we have expected for 190 rupees a night? No towel, sheets, soap or peace, but at least there were four separate lights in the tiny room.

I then succumbed to my first mild bout of Delhi — or, more accurately, Pragpur — belly. I knew I shouldn’t have eaten that tomato sandwich. Rather than allow ourselves to be depressed by our newly straitened circumstances, we decided to have lunch at the Tibetan restaurant opposite.

For the first time we saw lots of dirty, disoriented-looking Western travellers, most of whom looked rather undignified in their mismatched ethnic outfits and ridiculous haircuts. Many looked positively emaciated. Some in the restaurant could only glare and look sullen. Perhaps months of living on a few rupees a day, sleeping in dormitories and travelling on standard buses had ground them down.

Even a table of normal-looking Australians and Americans, rather than simply dividing their bill equally, worked out who owed 18 rupees, who owed 26, etc. — a difference of at most ten pence per person. I hope things don’t come to this.

The food was good. Alex was very daring and ordered a cheese momo, which turned out to be a tasty glorified dumpling. I had vegetable chow mein. The whole meal cost less than one pound, including water.

We then walked down to the monastery through streets and paths teeming with dignified monks fingering their prayer beads — which made the scuzzy-looking travellers seem even more out of place. The monastery itself was something of a disappointment: built in 1989, it was quite modern apart from its prayer wheels.

We decided to walk on and discovered a beautiful temple with views of the valley stretching for miles. It was festooned with hundreds of prayer flags and wheels. Monks and Tibetans walked along spinning the wheels while moving the beads through their fingers. As well as the regular wheels, there were two enormous ones that rang a bell with every revolution.

We walked back into town past cows, that seem to be the locals’ idea of rubbish recycling. One was perched four feet up on a plinth, munching away at refuse. I look forward to seeing if it’s still there tomorrow. Another was standing facing downhill at a 45-degree angle with nothing but infinity below.

It was certainly braver than Alex, who clings to the mountain side of the paths, afraid that vertigo will pull her over the edge to Dharamsala below.

Back to the hotel, the loo, a call home and dinner in the Chinese restaurant, where I am now writing this diary. Great stir-fried vegetables and music on the hi-fi. Blissful — except for the disgusting malaria tablets. Thank goodness for Olly’s Minstrels, now strictly rationed for medical emergencies.

Monday, 4th November - McLeod Ganj

We both had an uncomfortable night. The beds were rock hard and the pillows overstuffed with straw. It was cold, and Alex slept fully clothed. I was continually awoken by barking dogs and decided to get up at six, going for a walk through the village to the monastery and back via a hillside path leading past smaller individual houses — mostly occupied by monks, who seem to make up the main population of the town. What look like apartment blocks are either missions or monasteries for different orders of monks.

I returned to find Alex washed and scrubbed, and after having a shower myself we went in search of breakfast. As Richard Gere’s favourite haunt was full of dodgy-looking travellers, we tried the Lhasa Restaurant, ordering milk tea and banana pancake. Milk tea turned out to be hot milk with a tea bag in it — a bit grim first thing in the morning. The pancake was more successful: a one-and-a-half-centimetre-thick fried bread cake with slices of banana inside.

A strange Englishwoman with a bizarrely high voice, dressed in thick woollen tights and other eccentric clothes, came in and started arguing with the owner, demanding to make her own coffee. She was obviously barking mad. Also in the restaurant were a number of Westerners in their forties and fifties, dressed in similar odd garb. One, a tall man with long grey hair, was wearing a turban. We decided that one night at 190 rupees was quite enough, lest we end up looking as sullen as the travellers around us.

We had been recommended a hotel called Cloud’s End Villas by Mr Lal at Pragpur, but I had heard it was expensive. I called and was told it was 1,100 rupees a night. After saying that we intended to stay two nights, this was immediately reduced to 600 — a successful bit of inadvertent haggling.

As we didn’t need to check out of the Loseley Guesthouse until noon, we decided to walk up to Dal Lake. We never found it, but instead wandered through a beautiful pine forest, stopping to watch the monkeys and passing horses and cows along the way. We paused at the end of the valley and looked across it to see McLeod Ganj on the right and slopes of slate on the left, with terraced fields and cherry trees in blossom descending into the valley.

We stopped on the way back outside a school. The children came out and washed the exercises they had been doing from their wooden slates in the water butt outside. Alex spotted a beautiful bird with a twelve-inch-long tail.

We left the guest house and walked down the street to the taxi stand with our packs on our backs for the first time — luckily for only about two minutes. We had a terrifying ride down to the hotel, a blissful oasis compared to the hectic, cramped McLeod Ganj that we had just left.

We were met by three servants in uniform and shown to our room, which turned out to be a three-room cottage, separate from the main house, with its own beautiful terrace surrounded by trees and a lemon grove above it. The rooms are large and clean, the bed is soft and has sheets, and there’s a bath and towels in the bathroom.

We immediately relaxed into the surroundings and were brought tea. Lunch was served in a similar way to Chapslee: we sat alone in the dining room — again, the only guests — and were politely served delicious vegetarian food, probably the best so far.

After reading in the sun we went for another walk up hillside paths, past monks muttering mantras while fingering their prayer beads. This walk was two hours long, and we didn’t collapse on our return. Perhaps we’re getting fitter. Tea was followed by a hot bath accompanied by beer (and a giant spider, which has rather worryingly since gone missing). A large dinner followed.

Tuesday, 5th November - McLeod Ganj

A relaxing day. We walked down to Dharamsala, visited the Art Museum to see miniatures of the Kangra School, and had trouble buying stamps. After an unsuccessful attempt to find the Dalai Lama’s library, we trudged home to rest.

Wednesday, 6th November - McLeod Ganj

The twenty-minute walk up to McLeod Ganj took one and a half hours. We recovered by lunching on momos and vegetarian chow mein before walking back. I saw what seemed to me to be a path to the library — it turned out to be a steep path to almost nowhere. Alex was unimpressed, but after getting directions we were back on track — the same track we’d given up on the previous day.

I was pleased to be able to use my Leatherman tool to remove the ten staples holding together the 5,000-rupee bundle I’d picked up from the bank. We’ve also used our torches during two power cuts. I’m looking forward to finding an opportunity to make use of the roll of gaffer tape I brought along. Alex wouldn’t let me use it to patch up a plastic bag to turn into an improvised sick bag for tomorrow’s bus journey.

At 6.30, Alex started feeling unwell. This unfortunately developed into a very nasty case of food poisoning with vomiting and diarrhoea, which left her exhausted and weak.

Thursday, 7th November

Due to Alex’s condition, we’ve postponed our plans to leave for Mandi this morning. She’s spent most of the day reading and is still not feeling 100% by evening.

Mid-morning I walked into Dharamsala to change the bus tickets. Hopefully, walking up and down hills for two or three hours a day might make me fitter — or even thinner. Alex’s illness is doing the latter for her. I bought provisions for lunch: 18 rupees bought about twelve bananas, and 54 rupees — about a pound — bought a family pack of Kit Kats and two large bags of crisps. Alex managed to eat a little, and we both fell asleep.

At 3 p.m. I left for a final — and at last successful — attempt to find the library, which I happened upon by chance. It’s set among a complex of flats, houses and government buildings — very clean and peaceful compared to McLeod Ganj or Dharamsala. Each ministry — Health, Information and Foreign Affairs, House of Representatives, Education, etc. — has its own building. The library itself was colourfully decorated in Tibetan style, although the structure was relatively modern.

There seemed to be lectures going on, and Westerners and monks mingled and debated on the library roof. While I was there, most in evidence were elderly Tibetans, mainly women in their traditional costume — long, dressing-gown-style coats with wide sleeves and colourful striped aprons. They wore extensions and beads in their two plaits.

I returned to tend to Alex and on the way met a local Indian boy who carried Tibetan prayer beads. I asked him about them, and he told me he was a Buddhist, although his parents were Hindu. He took off his hat to show me his cropped monk-style haircut. As we approached Cloud’s End, he impulsively took off a string of prayer beads and gave them to me — a gesture I found rather touching. Finally, we packed, and Alex nibbled on a bit of solid food before an early night.

Friday, 8th November

The big bus journey.

Our “luxury coach” turned up and brought back memories of my prep school bus — only rustier and with tinted windows. Our rucksacks were put in the boot. All I could see was a thick — about half a centimetre — layer of dust on top of which the bags were thrown. Fortunately, the bus wasn’t full, so we grabbed two seats each.

Initially, the journey was very bumpy as we wound down into the Kangra Valley. I had seats behind the back wheel to start with so I was bouncing up and down. However, after a while the roads improved and I got a seat nearer the front. It wasn’t too bad, and the views were incredible throughout. The only frustration was the frequent stops to pick up both passengers and packages. The bus seems to double as an unofficial postal service.

After six hours we passed through Mandi, which sits astride the Beas River — a river we followed all the way to Manali. It flows through a dramatic gorge, halfway up which a dam has been built, and across the top of which the bus drove. As expected in India, there was a large army presence and signs prohibiting photography. The dam has created a turquoise lake, the surface of which lay at times 300 metres below us. Pretty exciting on a single-track road.

The walls of the gorge were covered with pine trees as well as palms and banana trees. Later still, there was a curious mixture of pine and cactus. Kullu, eight hours into the journey, seems to be a sprawling mass of bazaars, tiny shops, dirt and noise. We’ll have to work out whether we really want to stay there.

Night fell just as the roads worsened again. The practice in India seems to be for vehicles to leave their lights off until it’s completely pitch-black, which gave us an exciting frisson as buses veered towards us out of the gloom. At 7 p.m. — incredibly, an hour earlier than scheduled — we arrived in Manali.

Our first impressions weren’t great. On the south side of town sits a long row of “luxury hotels,” all of which look identical. The main thoroughfare was swarming with the usual tiny shops, peanut sellers, rickshaw drivers, hustlers, and stores selling Kullu shawls — a local speciality. The shops here seem to have stockpiled enough to take them into the twenty-first century and beyond.

The moment our bus stopped, hotel touts crowded round the doors. Like film stars through paparazzi, we pushed our way through to be reunited with our bags. These were handed the two feet from the trunk to our hands by a local urchin for a fee of five rupees. My bag, in particular, was totally coated in thick dust. It appears that a hole in the bottom of the bus had let in vast amounts of dust thrown up by the wheels. Once I’d got it all over my trousers, we found an autorickshaw to take us to the hotel we’d picked from the Lonely Planet guide.

This was allegedly a fine old Raj building with good facilities — “a good choice.” In daylight, we discovered that at least the first phrase was true. It’s set in a beautiful orchard, although fairly dilapidated. We were, however, in the modern block next door. On arrival, a couple of people standing around seemed amazed and bemused that we were asking for a room. They summoned the corpulent owner, who also seemed unimpressed. His “discount rate” was 440 rupees a night — fixed whether we stayed a night or a week.

Because it was late and freezing cold, we agreed. We soon noticed why he might have appeared disgruntled at our arrival: a rather seedy game of cards was in progress, the players surrounded by piles of banknotes.

As he led us to the room, he said there would be no hot water until the following morning. He unlocked the door to quite a large space that was the same temperature as outside. When we commented on this, he said it was too late to light a fire. The whole room was coated in a thick film of dust.

We locked our rucksacks in a cupboard and went straight out to dinner, wearing all our layers, including hats and gloves. Alex wore a fetching sarong around her head, which made her look like a Hezbollah terrorist’s mistress.

We went to a restaurant that the Lonely Planet guide had recommended should be booked in advance due to its popular. Four tables were occupied — one by a fairly disturbing group of stoned Austrian hippies, a couple of whom looked close to death. The food was passable, but we were distracted by a particularly drunken, scraggly Austrian’s attempt to make conversation with everyone at nearby tables. We kept our heads down and escaped back to the guesthouse, by which time the room had the ambience of a meat freezer at Smithfield.

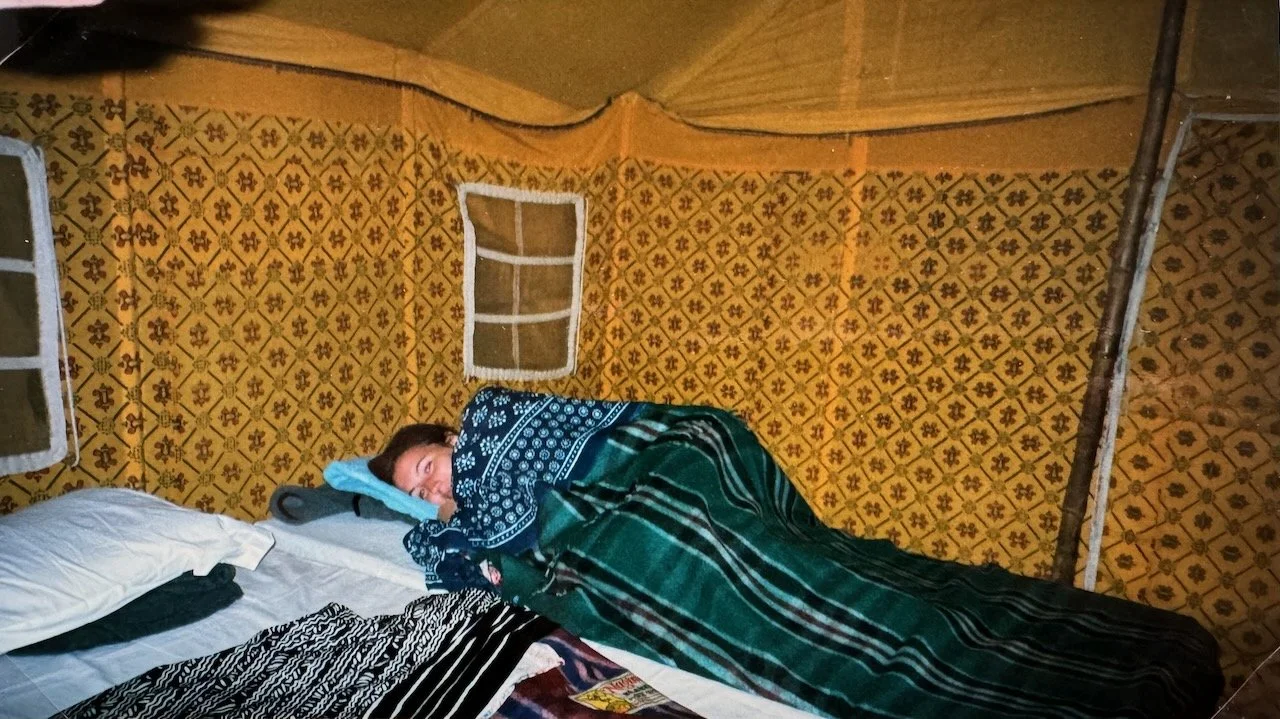

After almost getting stuck to the frozen loo seat, we prepared for bed. Alex went in fully clothed. I foolishly imagined that long johns, a T-shirt and a pullover would suffice. Two hours later I woke up shivering, my legs in particular frozen. I got out of bed to fumble for more clothes. Alex almost jumped out of her skin, thinking I was an intruder ready to rifle through her drawers.

She told me to put on full kit, so I pulled on trousers, fleece and socks. We survived the night, although it was largely sleepless. The previous evening I had already been fantasising about the warm, twinkling lights of the luxury hotel on the hillside above us. This is where we immediately set off for breakfast — and to look at a room.

Saturday, 9th November

The Shingar Regency is in fact rather jerry-built, but it had a bath, towels and loo paper — all missing the night before — as well as a television and a balcony overlooking the town. After a long soak in the bath to restore our core body temperatures, we walked down to town on a path that passed through a camp of tents inhabited by locals wearing even brighter clothes than usual for Indian women, including brightly patterned skirts.

It took quite a while to sort out our plane tickets from Kullu to Simla, and then we had a disappointing thali in another of Lonely Planet’s recommended restaurants, which, as well as being shabby, was frequented by yet more scabby, druggie-looking Westerners.

We walked back up the hill to visit a Hindu temple in the pine forest that surrounds the town. It was decidedly spooky — built entirely from wood. We stepped inside and noticed blood, feathers and goat’s fur smeared over the walls and ground, and a hut next to the temple where something, probably an unlucky goat, was being hacked to pieces.

We beat a hasty retreat to the safety of our hotel room, and as the sun went down discovered that the heating didn’t work. Hopefully the single-bar fire will keep us from freezing — although I suppose there is the possibility we might burn to death instead.

We kitted up in arctic gear and headed back to town through a power cut; luckily, we had our trusty Maglite to guide the way. We visited another allegedly “bustling” — but in reality completely deserted — restaurant, the Mona Lisa.

Sunday, 10th November

After a good night’s sleep — apart from nearly strangling myself with the bedding and Alex being mysteriously covered in red bites — we had breakfast on the sunny balcony before heading down to town. We bought a picnic lunch: four bananas and a big bag of peanuts for ten rupees, and two bags of crisps, then went to wait for our luxury coach to the Rohtang Pass.

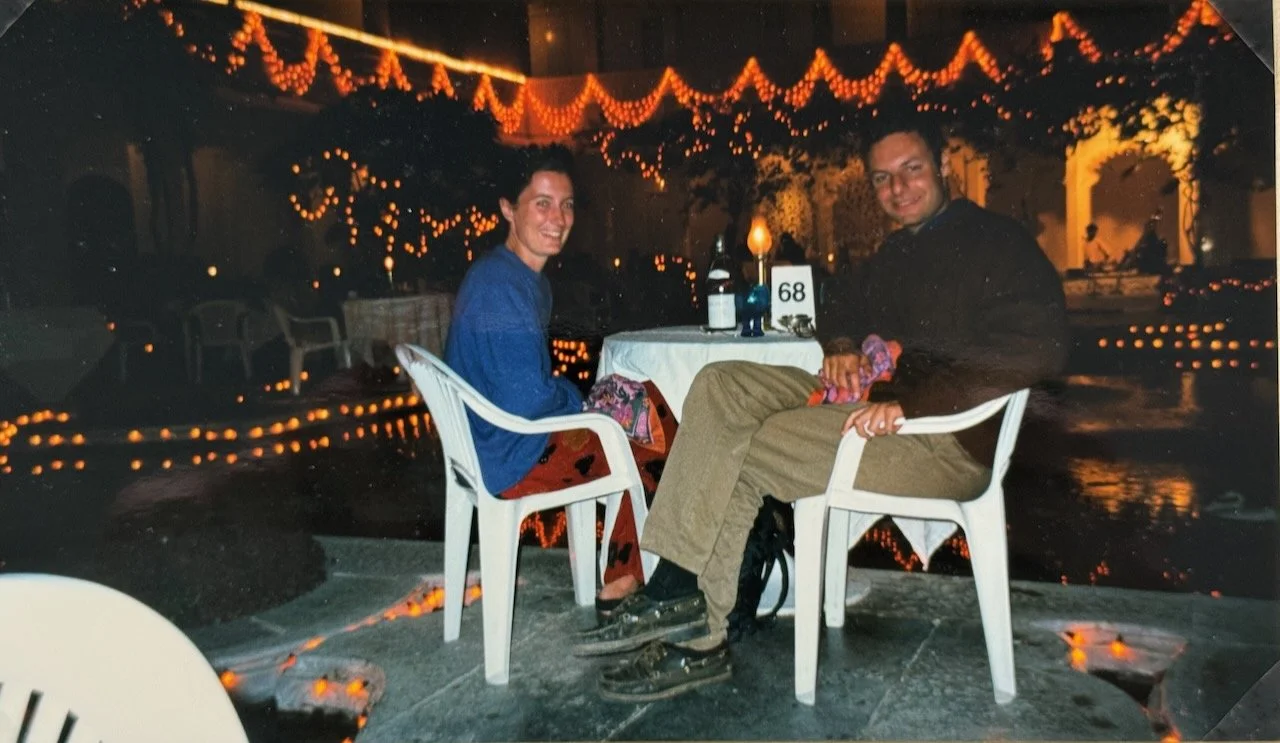

Today is the start of Diwali. The streets are busier than ever, with stalls selling colourful and extraordinary-looking sweets — the traditional Diwali gift — as well as fireworks and garlands of marigolds. Every car, autorickshaw and coach was festooned with them, even the shopfronts.

Our coach really was luxurious. Our fellow travellers were middle-class Indian families on holiday with their children. The idea behind the trip was to tramp about in some snow.

Although we’d been told the day’s activities would take from 10 a.m. to 5.30 p.m., we hadn’t really considered the transport implications. The Rohtang Pass is 13,000 feet above sea level and reached by an extraordinary road carved into a very steep mountainside. We rose slowly up the mountain, turning around blind corners and hairpin bends on the single-lane road.

Looking up the mountainside, we saw coach after coach winding away into the heights. For much of the journey the road surface was fairly good, but the worst potholes — or complete absence of tarmac — always seemed to coincide with the most vertiginous drops to our left or right. At one point, we drove straight through a river; the bridge across it was a tangled wreck.

About halfway up, we stopped at a stall hiring Wellington boots and fun-fur coats of every colour and hue — including leopard print. Our fellow travellers looked fairly absurd, and we decided we’d be fine with just our gloves and fleeces.

We stopped at a semi-frozen waterfall, which caused wonderment among the Indians, many of whom might never have encountered ice or snow. Men and women posed for photos in front of it, dressed in the local tartan-like women’s costume stretched over their enormous fun-fur overcoats.

After stopping for our picnic by a Hindu temple — which, for some reason, was wreathed in Tibetan prayer flags and surrounded by a shanty town of restaurants and stalls — we reached the summit. There wasn’t a great deal of snow — more like icy slush. However, the view was epic. The Indian tourists — we were the only Westerners up there — seemed to be having a whale of a time. Alex and I, meanwhile, were freezing in the biting wind blowing through the pass from the direction of Tibet. We trudged around for a bit, occasionally seeking shelter behind a bus. Alex had her multi-purpose sarong tied around her head, while my ears were becoming increasingly painful.

Freezing at the Rohtang Pass

We were supposed to be leaving at 2 p.m., so at 1.40 we decided it was time to find some warmth in the coach. The only problem was that it wasn’t there. We walked up and down for twenty minutes, wondering whether it had left us to our freezing fate. Then we bumped into a family from the coach — at least we weren’t the only ones stranded.

Alex was in a bit of a panic and kept wandering off on her own, until I’d find her standing somewhere looking anxious. After a while, all the bus passengers were reunited — but still no bus. I sought refuge from the wind in the lee of a minivan. When the occupants saw us, they beckoned us in — a blissful interlude from the gale. We were immediately offered a joint, Manali being famed in certain circles for the quality and quantity of the cannabis that grows wild on its hillsides — which may account for the number of cadaverous hippies riding around on big motorbikes. I politely declined the offer.

When the bus was half an hour late, we decided to try and get on another one heading down the hill, as the crowds were noticeably thinning. However, our bus eventually appeared around the corner — forty minutes after the scheduled departure time. Rather than being angry, our Indian co-passengers thought the whole thing was a huge joke.

All I could do to register disapproval was not smile at the grinning driver. So off we set down the hill, past stunning views of the hills and mountains, descending the steep mountainside and wondering once again whether we had put ourselves in harm’s way. On the way down, the bus had to crawl around a misshapen lorry lying on its side — it looked as if it had fallen from somewhere above.

At 5.30 we were back in Manali, and Diwali had started in earnest. Firecrackers were exploding all around us, putting Alex, who can be of a somewhat nervous disposition, into a mild state of panic. We retired to watch the flashes of the firecrackers and rockets from the safety of our hotel room. The whole town was erupting with noise and light, and it continued unabated for hours. The bangs were still rending the air the following morning, when a pool of smoke hung over the town.

We had some pretty good food in the hotel restaurant, which unfortunately didn’t serve alcohol, and then went to watch other guests create havoc in the entrance courtyard by letting off rockets and bangers. Unlike in the UK, they had no qualms about re-approaching fireworks once lit, and when you light a string of firecrackers, they jump and explode all over the place. Even more amusing to the locals was a rocket that took off, immediately arced back to earth, and missed the man who lit it by inches.

Monday, 11th November

We had a leisurely morning — breakfast on the terrace, a long bath, watching Spice Girls videos on V, the Indian version of MTV, while reading our novels. For some unknown reason, I got a call from V, asking me something in Hindi. Apparently, I was being entered for a big game show if I could answer a question. I was all ears, fingers on buzzers — but unfortunately, I didn’t know the surname of the famous Indian pop star. The girl put the phone down in disgust.

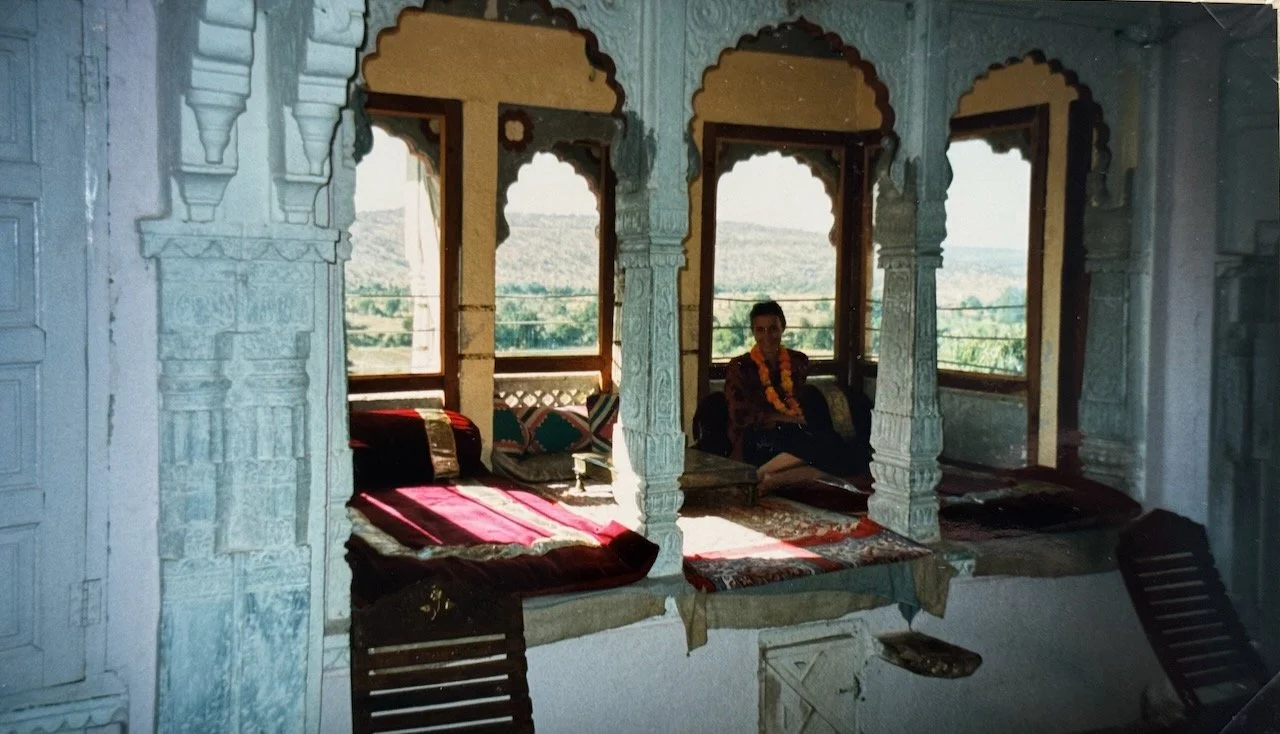

We took a taxi the 22 kilometres to Naggar Castle, our next hotel. At last, we found ourselves in almost a proper car — a Maruti Suzuki four-wheel-drive jeep. The road was little more than rubble in places where the Beas River had overflowed its banks and washed it away. We crossed the river and climbed the hill to the castle — a very imposing building dating from the 1500s, when Naggar was the capital of the Kuth Valley. Its walls are four feet thick, the rooms enormous, with fifteen-foot ceilings — but fairly threadbare and very cold.

We explored the village and ordered some pakoras in an open-air café. Small Hindu temples are dotted around the valley, some in the process of being built, all with roofs covered in drying maize. There are fantastic views of the valley from the balcony surrounding the castle. Once the sun disappeared over the mountains, the temperature plummeted. Luckily, we managed to borrow a heater, which made some impact on the enormous room.

We played Scrabble, and Alex won. We decided to find some dinner. The castle’s dining room was unlit and freezing, so we went to a nearby hotel, where we huddled around a stove in an otherwise cold room. It was fed with a single twig every half-hour or so. We met some other travellers, including a taciturn Swiss man — he’d been there for four months — and a more positive Scottish couple. We made it through a cold night.

Tuesday, 12th November

We walked up to the Roerich Gallery “a gallery housing a collection of paintings by Nicholas K. Roerich, a Russian painter, philosopher, and explorer who created thousands of paintings inspired by the beauty of the great Himalayas”. It was not terribly inspiring, although Alex thought it was okay. We then continued around the hill, eventually coming across four local men sunning themselves, woven baskets by their sides. One of them said, “Rest!” — and how could we refuse? We sat and tried to communicate. They found us — especially me — very amusing, and enjoyed trying on my glasses and, against her will, Alex’s Lip-salve. I promised to send them a photograph of themselves.

We returned to the hotel for lunch, which was pretty good, then walked down through the village, which is very picturesque and full of naughty children who impressed on us that they could say “hello” and “bye-bye.” On the way back up, I was beckoned to a Hindu temple by a man in whose restaurant we had eaten the day before. I joined him; Alex fled. I was told to take off my shoes and sit cross-legged — no easy feat for me. It turned out that today was a festival celebrating the god Vishnu.

We were each given a plate made of leaves sewn together with straw and a cup of water. Someone then put handfuls of rice on the plate, followed by vegetable curry. My neighbours were having huge portions. Having just finished lunch, I tried to avoid the second handful. For the first time, I ate with my fingers, without even the insulation of a chapati — quite a strange sensation. I was given a lesson in how to lean forward and scoop the food upwards into my mouth.

A second helping was forced on me, and when I was seen wavering, I was told I had to finish it all. By this time I was feeling uncomfortably full and wondering where the food had been cooked. I managed to clear the plate, only for it to be replaced by a handful of sweet rice. There was no religious ceremony — just a line of people sitting cross-legged, eating in front of an eighteenth-century temple, which was interesting enough. I staggered back up to the hotel clutching my stomach and recovered as the sun dipped over the mountain.

We fled to our room at 4.45pm and didn’t leave until the following morning. I couldn’t bear to eat any more, and neither of us was keen to leave the relative warmth of our single-bar heater for the cold restaurants of Naggar. Instead, we tucked ourselves into bed wearing two T-shirts — one short- and one long-sleeved — a pullover, long johns and socks. I woke up at 3 a.m. and read Captain Corelli’s Mandolin until six.

Wednesday, 13th November

We spent a relaxing morning at Naggar Castle before getting a taxi to Kullu, which took us along the east bank of the River Beas on a road that wound through farms and villages. On the way we saw our first funeral ghat by the side of the river.

Hotel Sidharta is pretty good — and only three times the price mentioned in the Lonely Planet guide. We went to change some money at the bank, which took fifteen minutes of form-filling. The completed forms and my passport were inspected in depth by both the desk clerk and the manager.

As with hotel check-ins, passport numbers, dates and places of issue and expiry — and the same for visa information — are all laboriously taken down twice. At least three people were involved in changing two traveller’s cheques.

The town is more interesting than it had appeared when we drove through it last week. Every kind of shop and business operates along the main streets: sewing-machine dealers, printers, corrugated-roofing suppliers, pots-and-pans merchants, suitcase shops. As with market stalls, for some reason shops selling the same products are often grouped next to each other.

We went to a restaurant — one of the very few in town — with real tables (although only two feet high), mauve curtains, and men sitting around smoking and drinking tea, including two more dodgy-looking hippie-ish travellers. The food was good at the time, although it was followed by indigestion later.

Afterwards we walked up to the Maidens, a big, grassy, dusty area used for fairs and markets. Today was clothes-and-duvet day: fifty-odd tables covered in every kind of clothing and fabric. One quilt stall had hundreds on display — how many were they expecting to sell?

Thursday, 14th November

The day we were due to fly to Delhi: arrive at 1.30 p.m., organise a few things and have a pleasant evening with Andrew Studd. The reality was that we arrived at the airport at 9.30 a.m. and patiently waited for check-in at 10, when we were told the flight was delayed for three hours due to technical difficulties. This was somewhat aggravating, as the airport had no facilities — and neither did the nearby village.

We sat by a dusty roadside inhaling diesel fumes. After an hour we returned to the airport to ask if there had been any developments. The local manager said he was calling Delhi to find out. The news: the flight was cancelled. We were informed that we could get a refund and instead take a taxi to Delhi — a fourteen-hour drive away.

This was so extraordinary it took a few moments to sink in. Weren’t they going to charter another plane? No. The next Jagson flight was five days later, and the other airline’s flights were fully booked. The airline refused to pay anything towards travel or hotels.

The manager shrugged and said it wasn’t his problem. Initially, he told me I’d have to return to Manali to get a refund on the Kullu-to-Simla leg. I saw red, shouted at him, and he relented. Other passengers were understandably going berserk, one man screaming at the manager. Every time his phone rang, he picked up the receiver and slammed it down. Eventually he handed it to his wife for safekeeping.

Our carefully laid plan to avoid a long and terrifying drive down the mountain had been dashed. We couldn’t even get a bus as the next one didn’t leave until evening. So — a taxi it was. We decided to stop in Chandigarh for the night; six hours at a time was quite enough. At least we could take a bus on from there, as the taxi for the first leg alone cost 2,400 rupees.

The journey began okay, although it was disconcerting to stop at a garage and have the car jacked up with us inside while mechanics peered underneath. Once past Mandi, the road became very windy with deep ravines to one side. Our driver seemed keen to break some kind of record and overtook buses and trucks at every opportunity. The latter were the bane of the road — belching thick black diesel smoke, limited to 40 km an hour and unable to manage more than ten kmph uphill. On blind corners and the brow of hills we had several near-death experiences as juggernauts hurtled towards us.

At one point he swerved to avoid an uneven part of the road, heading straight for the cliff before just righting himself. Another time he crashed into the back of a jeep that had braked to avoid running over a dog. We passed two wrecked lorries: one had left the road and smashed into a tree and was being hauled out by two tow-trucks; the other lay on its side, apparently having fallen down from the road above. Without seatbelts — which don’t exist here — it was hard to imagine the drivers had survived.

I was overcome with relief when we hurtled down the final hill to a sign reading Welcome to Punjab, and we hit the plains and long straight roads. Punjab is very green and full of activity. The farms seem well-tended, and unlike Himachal Pradesh, where people appear to spend much of the time standing or sitting by the roadside watching life go by, this was a hive of industry. The majority of the population is Sikh, and they really do look different to Hindus — beyond turbans in pastel shades and the beards. Apart from anything else, they seem taller. Punjab is the richest state in India, even though it has only 2.5% of the population. Twenty-two per cent of the country’s wheat, ten per cent of its rice, and a third of its milk are produced here.

We reached Chandigarh at rush hour, the roads seething with bicycles, mopeds and rickshaws — and especially tall cows. Chandigarh was designed in the 1950s as a new town by Le Corbusier. It’s laid out on a grid system, split into numbered sectors, and is a huge, bustling city full of shops mainly selling expensive consumer durables. Punjab is the richest state in India, which might explain this.

We followed the Lonely Planet’s recommendation and went to the Aroma Hotel, listed at 300 rupees for a double. On arrival we discovered the price had risen to 1,200. Too frazzled to look elsewhere, we were shown to a rather shabby room. Neither the receptionist nor the hotel’s travel service could give us any information on buses to Delhi, helpfully suggesting we walk to the bus station to find out. I told them I was unimpressed, and we stormed off — running terrified across wide thoroughfares crammed with vehicles, but with no zebra crossings.

We weren’t able to buy a ticket, but at least we found the timetable and were told we were sure to get a seat. We’ll see.

Friday, 15th November - Chandigarh to Delhi

And we thought yesterday was a nightmare. We woke early in a room that smelt of damp and stale piss — obviously it’s not called the Hotel Aroma for nothing. As we crawled out of bed, a cockroach scuttled across it, and Alex’s bedbugs looked as if they were trying to consume her as they marched across her skin.

We decided to take the 8.15 bus to Delhi. Breakfast was included and supposedly began at 7.30, so we thought we had time to grab it. In fact, they only started preparing it at 7.30. All we got was a foul cup of cardamom-flavoured tea with a skin on top and cornflakes in hot milk. The toast Alex had ordered was pounced upon by two corpulent Indian businessmen. I had an interesting curried-egg omelette and potato curry.

We’d asked the hotel to order a taxi to take us the two-minute drive to the bus station, but the receptionist gave the job to one of his cronies, who tried to charge us 50 rupees — a complete rip-off. Alex stopped me from storming out to find another taxi, as our bus was about to leave, so we reluctantly haggled him down to 40.

At the bus station we pushed our way through touts to the window where we’d been advised the night before we could buy tickets. The man there sent us back to the bus platform, where we eventually succeeded.

The highlights of the seven-hour bus ride were: a numb arse; a car smashing into us on a roundabout, which the driver didn’t even seem to notice; the occasional slow crawl as lines of traffic overtook donkeys and carts while narrowly avoiding oncoming lorries; and a few crashes — notably a bus on its side, with passengers still crawling out. Perhaps this is how Godard’s Weekend and J.G. Ballard’s Crash were inspired. We also passed the massive site of a religious festival starting the next day — a tent city that stretched for miles.

The bus arrived in Delhi an hour late. We had a few things to organise, so it was important to get to New Delhi quickly. We ignored the touts and queued for twenty minutes at the “fixed fare taxi” stand — at least, that’s what it called itself. Once at the kiosk, the man looked incredulous: of course, it was only for autorickshaws. Taxis were paid by meter.

We found a taxi whose driver I immediately began arguing with. His meter worked, but he wanted a fixed rate. Again, Alex pointed at the time and made me give in. We drove past Old Delhi, thronged with people — many poor or begging. Outside the Red Fort, hundreds of coaches stood with roofs piled high with belongings, surrounded by a heaving mass of people.

New Delhi is like another world: wide avenues lined with enormous colonial bungalows and embassies. At last, after two fairly hellish days, we were arriving. But it wasn’t over yet.

We had the street number for Andrew Studd, with whom we were staying, but not the flat number. The security guard wouldn’t let us in. I showed him the address and tried to get him to help, but he just stared at us blankly and suspiciously. I noticed a sign for the Estate Manager’s office, so I forced my way past the guard, leaving Alex in the street to watch the bags.

The Estate Manager wasn’t in his office, but three employees were. I showed them the address — more blank looks. I asked to use the phone; they refused. After two days of travel and now finding myself thwarted literally feet from our destination, I really thought I was going to lose it. Even offering 50 rupees wasn’t enough to persuade them to let me use the phone to discover Andrew’s flat number. I don’t think I’d experienced impotent rage before, and I hope not to again for a while. My predicament was clearly a source of great amusement. I was told to take a seat and wait. I sat with my head in my hands.

Meanwhile, Alex appeared, having been made to lift both heavy rucksacks into the guard’s hut while they looked on. The guards were now holding the bags hostage, presumably in case we were terrorists.

Eventually they put me through on the phone and, to our great relief, we got the flat number at last. Andrew’s flat-cum-office is enormous and opulent — stylish, spacious rooms, all mod cons, a cook, a driver, and a swimming pool. He was looking busy but happy. Unsurprising, given his comfortable lifestyle.

We had to leave almost immediately to pick up my Amex card from the travel office and our train tickets from the Imperial Hotel. The credit card was waiting for me and everything was arranged in two minutes. Perhaps my faith in India was being restored.

Unfortunately, it was given a cruel, if not fatal, blow at the Imperial Hotel. Their travel desk had been asked to buy us two tickets to Jaipur for the following day. They hadn’t been ready when we left Delhi two weeks earlier, due to a computer malfunction at the railway booking office, so we’d asked the hotel to arrange and hold them until our return.

Initially, the men at the desk looked worried. They asked where we were staying and said the tickets would be delivered that evening — which sounded unlikely. Then they explained that the girl who’d booked them was away at an art class and had taken them with her, and that we should come back an hour later. Having already waited ten minutes to hear this, we left to find a beer and nurse our persecution complexes.

It was hard to believe it was happening again. I asked to see the hotel manager. A man was pointed out to me, who later turned out not to be the manager at all. A new story began to emerge: we had supposedly made a mistake and asked for tickets for the 15th, not the 16th, so we’d missed our train. Our blood, having been at an even simmer, came to a boil.

When I returned to the desk, we were told to wait again as the girl still hadn’t got back. Alex went up periodically to threaten them, and after half an hour we’d really had enough and began creating a proper scene. The first “manager” fled — having seen me approach, he calmly rose from his desk, walked briskly toward the stairs and vanished.

I found another manager who was slightly more helpful. When the discussion between myself, Alex, the manager, and the owner of the travel desk became potentially embarrassing to other guests, we were at last led into the real manager’s office.

We demanded not just a refund, but some other form of redress — for instance, a car to Jaipur (though after two days of terrifying driving, I wasn’t keen). The sub-manager blamed the travel office and said he wasn’t authorised to act for the hotel. To the travel-office manager, the fact that the 1,600 rupees would be deducted from the 2,000-rupee salary of one of the staff seemed perfectly satisfactory — but it didn’t seem fair to me.

Finally, the third and real manager arrived, listened to our grievances, and at last put them right. They weren’t able to get us a ticket for the next morning’s train, so they made the travel office supply a car to Jaipur for free. Once Alex informed him that no one had ever said or implied that they were sorry, he also apologised.

We returned, exhausted and shaky, to the flat — though not before being taken to a completely wrong address. We had a great evening discussing India and everything else. We were given excellent gin and tonics and a delicious quiche with sterilised salad — supposedly washed in the same stuff used to clean babies’ bottles. We went to bed at midnight, our latest night yet.

Saturday, 16th November

As the hotel couldn’t get tickets, they sent a proper car with a good driver to take us along the hair-raising road to Jaipur. It started off as a motorway but soon dwindled to a two-lane road — luckily with a few short stretches of dual carriageway.

Today, in order of speed, came cars, buses, lorries, and finally camel-drawn carts. It was like being in a never-ending chase sequence from an action film, with vehicles missing each other by inches. We passed one very fresh accident — two lorries smashed head-on — only minutes after it had happened. Luckily, our driver was relatively sensible and didn’t take too many risks, although we did have to assume the crash position a few times.

The landscape changed from green plains to scrubby desert with the occasional irrigated farm. Camel carts were everywhere, and when we reached Amber we saw our first elephant. Amber and Jaipur looked staggering, and the Hotel Narain Niwas is fabulous. More of this tomorrow.

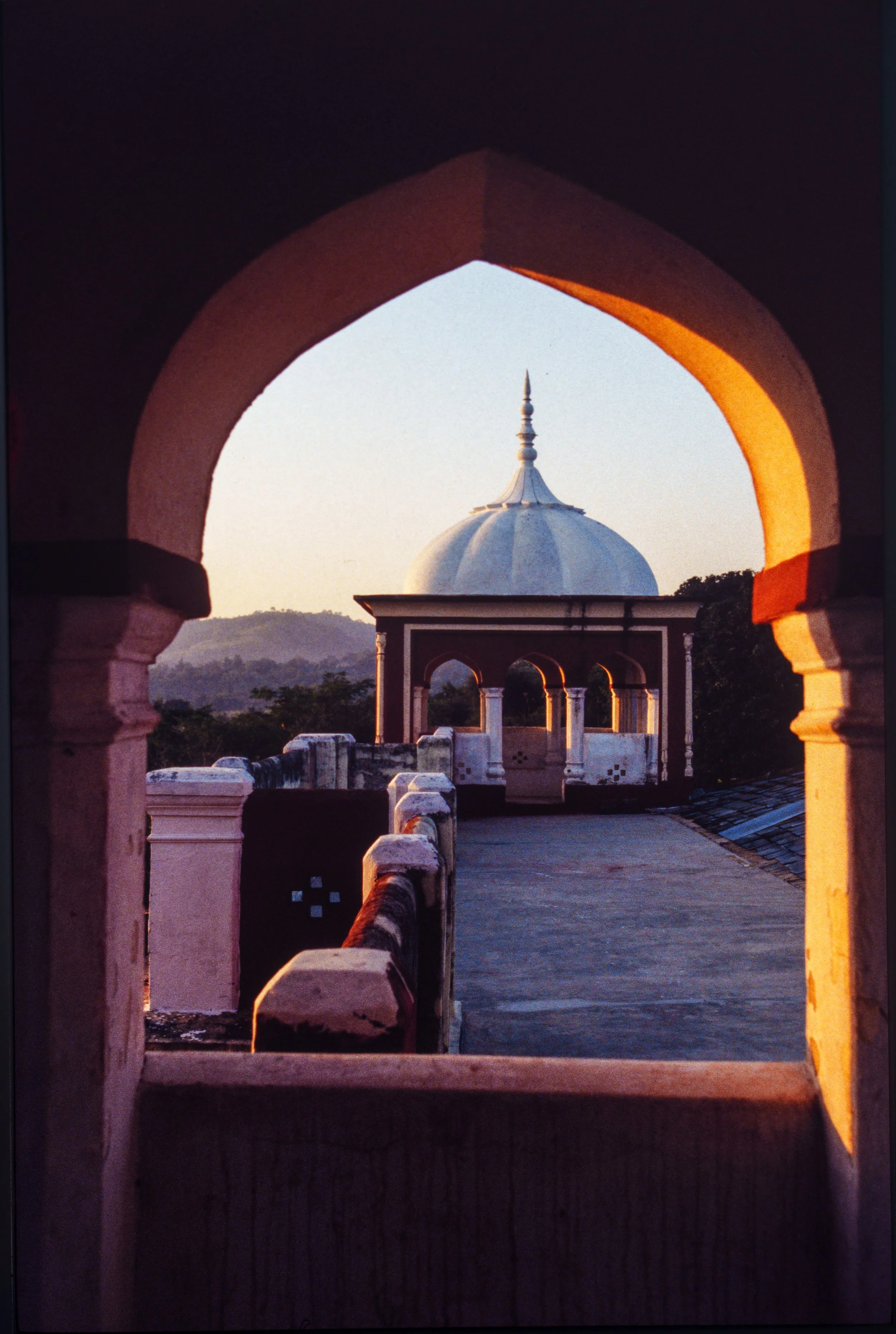

Amber Fort

We ate dinner in the hotel. The food was good, though the ambience was a bit university cafeteria. We went to bed early, and Alex collapsed immediately.

Sunday, 17th November

Narain Niwas is an old Maharaja’s palace — smaller than most of those liberally scattered around Jaipur — but beautifully redecorated. Our room is one of the new garden wings, built in the same style, with arches and brightly painted walls. There are quite a few mosquitoes around, so we’ve armed ourselves with mosquito coils and Autan.

After a disappointing breakfast, we decided to explore Jaipur — although first we thought we’d better organise some trains and accommodation for Pushkar. We found a rickshaw driver outside the hotel who ended up driving us around for the next two days. He was very amiable and, to our relief, didn’t drag us to any “craft cooperatives.” We paid him 200 rupees a day and couldn’t decide whether that was generous or stingy.

We queued for our train ticket from Ajmer to Udaipur for an hour — no movement for the first half. Various locals tried to push in, but we fought them off. The queue was reserved for foreign tourists, OAPs, and freedom fighters — and all they seemed to be fighting for was the freedom to push in.

Once we reached the front, we were told all trains were full. Meanwhile, the tourist office I needed was closed. We decided sightseeing might be easier and headed for the Palace of the Winds, followed by the City Palace — very impressive, especially the astonishingly intricate miniature paintings and the five-foot-high silver urns, almost as wide, made to transport water to England on the Maharaja’s trip in 1902. They are said to be the largest silver objects in the world. One gallery also displayed carpet rolls twenty feet wide and up to seventy-two feet long.

Next, we visited Jantar Mantar — the astrological gardens — a collection of surreal, monumental instruments. I decided to climb the tallest of them, but was so terrified coming down that I pulled a muscle in my leg. It hurts.

Lunch was at LMB, a bizarre 1950s restaurant straight out of Pulp Fiction. Afterwards we visited the Cenotaphs of the Singh Rajas, with its beautifully carved marble sculptures. A huge feast was being prepared at a nearby Hindu temple — aubergines and herbs being chopped, leaves ground into paste, and an enormous pan of lentils simmering.

After this, we were taken to what we were told was a block-printing factory but which turned out to be a showroom. We were given the hard sell but managed to escape. Tea on the lawn back at the hotel was followed by finishing Dark Spectre by Michael Dibdin — very exciting.

We then got lost walking to the Rambagh Palace, almost getting swept into an event at the local Rotary Club. We eventually found the hotel — stunning, enormous, meticulously maintained, extremely expensive, and somewhat impersonal. Built two centuries ago as yet another palace for the Maharaja of Jaipur, it is now a luxury hotel.

We had drinks in the Polo Bar — very smart — and narrowly avoided tripping into a fountain disguised in the middle of the floor. At 95 rupees a shot, we decided to push the boat out, though judging by the bill, tonic water was 120 rupees a bottle. If it had been cold, it might have hurt less.

Dinner was a delicious and generous thali in one of the restaurants. As we were leaving, the head waiter chased after us asking whether we’d lost anything. We looked at him as if he were mad — until I checked my pocket and found my wallet missing. I got the blame at first, but it turned out to have been Alex’s fault after all. Thank God it happened in the grounds of a swanky hotel and not on the street.

We asked for a taxi back to our hotel. The driver said he couldn’t leave the Rambagh grounds for less than 95 rupees. It’s a different world. We felt rather guilty to have spent 1,000 rupees — about twenty pounds — in one evening.

Monday, 18th November

Our planned trip to Amber was thwarted. We waited forty minutes — rather than the five we’d been told — only to discover that the car we were meant to use didn’t work. We gave up and decided to do some shopping and organisation instead.

First stop was Anokhi’s showroom shop — excellent, and although expensive compared to the bazaar, still very reasonably priced. Alex bought two shirts, dresses, trousers, four sarongs, and a large quilt for home. The latter is being sent back by post, which will take four months.

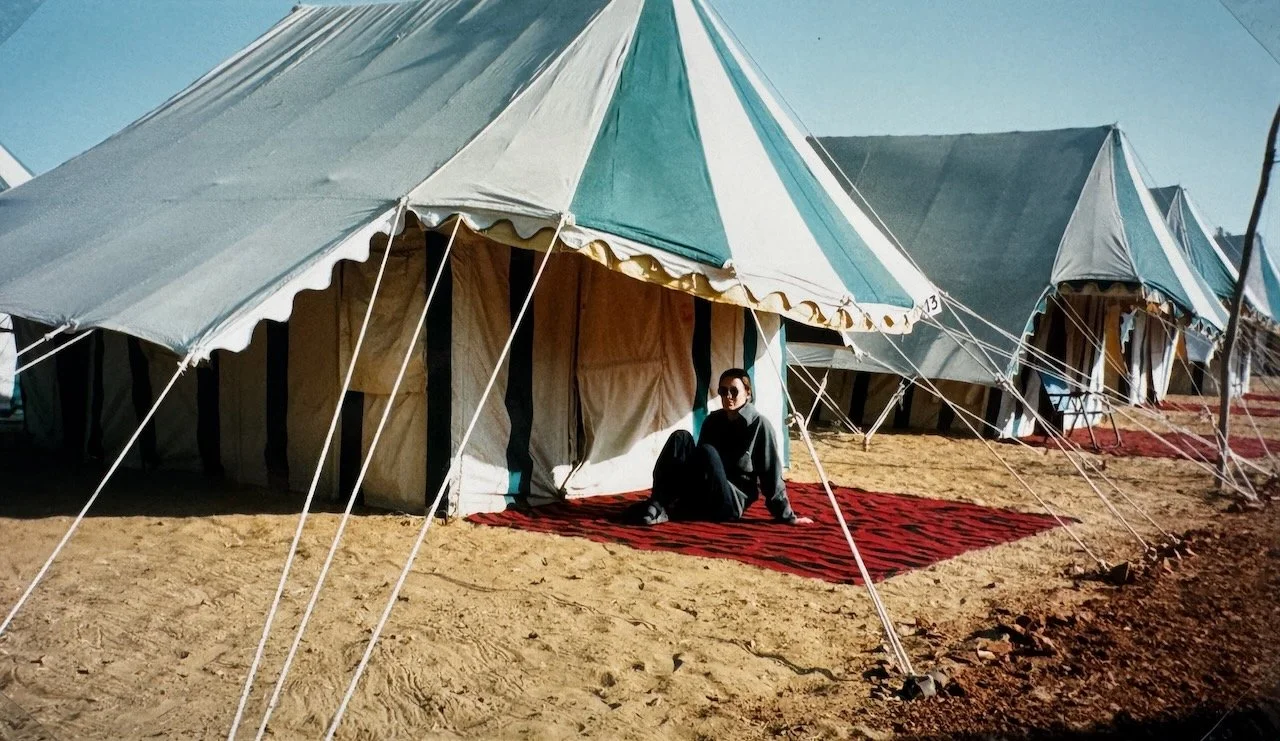

We managed to sort out our tent in Pushkar, bought flights from Jodhpur to Bombay and then on to Trivandrum, and arranged a car for tomorrow.

We sat by the pool at the Ashok Hotel, where I eventually managed to lower myself into the icy water, followed by lunch. We watched a table of four Indian businessmen being served gargantuan quantities of food — including a platter of rice that could have fed a family of twelve.

That evening, we took the same rickshaw to dinner — by which time the driver had apparently celebrated his good fortune by getting drunk. He was distinctly bleary-eyed when we set off and drove like a maniac, often refusing to let huge buses overtake. We arrived in one piece at Nem’s, a very good restaurant — clean, well designed and refreshingly calm.

Tuesday, 19th November- Sariska Nature Reserve

Our car to Sariska stopped at Amber. The lake palace reflected in the water was beautiful, and the fort impressive, if far too crowded with busloads of tourists from every country.

Sariska Palace is a huge — if not particularly attractive — series of buildings dating from 1892. It’s fairly shabby, though you wouldn’t know it from the prices. The cheapest room is 1,600 rupees; a plate of pakoras costs 50; even a piece of bread costs extra. One rupee in McLeod Ganj equals ten here.

We’re going on a two-and-a-half-hour jeep safari tomorrow, costing 550 rupees. In the public areas are stuffed tigers and leopards looking distinctly undignified, each surrounded by air-freshening balls — including in their mouths.

With no other accommodation nearby, the owners seem to be exploiting their captive clientele. We sat by the enormous — but too cold to enter — pool next to the crumbling pool house, and walked back via the ruin of a tennis court that once had several rows of tiered seating on one side. All that’s left is cracked concrete, two metal poles, and the faint ghosts of tram lines.

Back in our cold room I treated myself to a mandi. A new discovery: sitting in the bucket-style bidet to rinse my parts.

We left the room in search of a beer and came across a huge bonfire built in a brazier on the terrace. It was five feet across, and we huddled around it — our eyelashes singeing while our backs froze.

Dinner was a fixed-price 350-rupee buffet. There was no local option, but at that price we thought the food might at least be decent. It was appalling. Watery tomato soup was followed by stodgy rice, vaguely warm dal, cold saag paneer, sad and soft roast potatoes, dry-looking cauliflower I didn’t dare touch, and overcooked, congealed macaroni.

We would have been unhappy at 100 rupees, but this was a rip-off. Being the only hotel for tour groups at the park, they clearly felt free to serve any old rubbish to their captive audience. I made my displeasure known; the staff seemed surprised. “Nobody has complained before,” they said. Now it was my turn to be surprised.

I asked the leader of a large French tour group what he thought. He told me the food was poor and that he’d be informing the travel agency on his return to France. The next day, the receptionist claimed the same man had told him the food was very good. It’s hard to know whether the French or the Indians were being perfidious.

Wednesday, 20th November

We got up at 6.30 to be ready for our 7 o’clock jeep safari through the Sariska Nature Reserve. It was very good. We saw many different kinds of deer, as well as monkeys, wild boar, and a jackal. We didn’t see a tiger, but we did see tiger footprints — and they looked fresh.

We returned to the hotel and had breakfast at the RTDC Tiger Den, which — at a thousand rupees less per night and two hundred rupees less per dinner — was perfectly adequate. We decided to vote with our feet and move there for the second night.

We spent a lazy day reading in the garden. At one stage a local minister or some similar dignitary turned up in a smart car with armed escorts and held court on the lawn. Not feeling like another buffet for lunch, I bought a packet of biscuits.

As soon as I opened them, a monkey began giving me the evil eye, then started approaching. I stood up and shooed it away, at which point it bared its teeth and poised for attack. Luckily, one of the biscuits flew out of the packet as I gesticulated wildly. The monkey leapt towards my feet, grabbed it, and sprinted off. I was left rather shaken.

The caretaker then presented me with a big stick, which I shook at the circling, horrible, mangy beasts — with their unpleasant testicles, nasty nipples, and livid arses.

By seven we’d had enough of sitting in our freezing room and decided to look for the bar, which had been advertised on road signs most of the way from Jaipur. We found a padlocked door and went to ask for it to be opened. The manager shuffled off.

We stood around the lobby for a while until he reappeared, looking shocked to see us still there. “It’s open now,” he said, as if we should have known. We went down the steps — it was still locked. We sat on the chairs outside in the cold until another member of staff walked past and did a double take. “One minute,” he said.

Five minutes later, the same wrinkled old retainer who had given me the stick appeared and unlocked the door. The “bar” looked like a boiler room — two sad tables, a buzzing fluorescent tube above, and mosquitoes on all sides. The only plus was that the fridge was warming the room slightly.

At last we got our beer, which was at least cheap. We sat with our feet on the table, watching a large grey mouse doing circuits of the dustbins, and were joined by an English couple, with whom we chatted and later shared the surprisingly decent buffet dinner.

Thursday, 21st November

We got up early, as we were due to be picked up at 9.30 by the same taxi that had brought us, to take us back to Jaipur, where we’d catch a bus on to Ajmer.

We went into the restaurant. Two waiters were standing behind a table covered with metal buffet containers. They looked alarmed to see us at 8.15 — there was nothing in the containers. They offered to boil us some eggs.

At nine, a message was relayed to say the taxi would be an hour late as it was stuck in traffic behind a car. We sat in the garden and waited. An hour went by — and then another. The phone line to Jaipur was, of course, down, so we couldn’t call the hotel there.

We walked over to the Sariska Palace to see if they could organise a car. Being helpful and efficient, all they managed was a succinct “no.” The Tiger Den said they could provide a battered open jeep for seven rupees a kilometre — twice the cost of the Ambassador that had driven us from Jaipur. Not, I’m sure, that they were trying to take advantage of the situation.

They grudgingly agreed to the same rate as the Ambassador before discovering that they didn’t actually have a jeep available — although they claimed they could rustle one up in an hour. We’d by now discovered that an Indian hour could be interpreted in many different ways. It was now three hours after our scheduled departure and still no transport in sight. In high dudgeon, we trudged off to the bus stop — where, unexpectedly, things started going right.

A local bus appeared after twenty minutes, and there were two spare seats. It was comfortable, and people made space for us. In fact, it was almost as good as a deluxe bus — though those have seats that recline so far back the person in front practically kneecaps you.

I was offered — and gratefully accepted — peanuts from the man sitting in front of me, and we pulled into Jaipur bus station at 3.15. We jumped off and immediately bought tickets for the 3.30 luxury bus to Ajmer. I ran off to call the hotel to remind them of our booking, then bought a late lunch of bananas, peanuts, and water — which later, rather embarrassingly, leaked all over my crotch.

And then we were off — very slowly — to Ajmer. The journey took four instead of two and a half hours, thanks to an unbelievable amount of traffic: a never-ending stream of lorries and buses with their roofs piled high with belongings, and for some reason, at least one child’s bicycle precariously hanging over the edge of each one.

We stopped dead for twenty minutes a couple of times to wait for hideous pile-ups to be pushed off the road. One car had been concertinaed to three feet long, and as usual, overturned lorries littered the roadside — sometimes with surviving crew members sitting forlornly beside their crushed cabs.

We arrived at the hotel — another shabby RTDC place, again with inexplicably enormous rooms. This time we even got towels, sheets and a TV, so that was one up on Sariska.

Today, we were told, is a very auspicious wedding day in the Hindu calendar. Jaipur and Ajmer were full of brightly coloured wedding tents. One had a raised dais with two golden thrones for the bride and groom.

Atrocious wedding bands came out of the woodwork — principally brass bands with drummers, accompanied by a brutally amplified Casiotone keyboard, pulled along in what looked like a brightly coloured DJ booth. The band’s bearers also carried electric lights — all wired together and powered by two diesel generators on wheels, which brought up the rear.

There was one such band right outside our Ajmer hotel room, so I ran down to take some photos. The groom looked resplendent, if rather nervous, astride an extravagantly decorated horse. I was almost immediately invited to the wedding dinner, which I thought was very kind.

Although I would have loved to see an Indian wedding dinner,

a) we’d just eaten a rather good meal at the Mansingh Hotel b) Alex was waiting for my return in the room, and c) I didn’t feel I could impose on them.

It was a good end to an otherwise difficult day.

Friday, 22nd November - Pushkar

We breakfasted on grim tea and toast with thin, wine-gum-flavoured jam. They were out of butter. The hotel was very unhelpful about storing our bags, so we had to leave them at the bus station’s left-luggage counter.

On leaving, we reminded them that we’d be back the following night as arranged. Unsurprisingly, they said they were full and that we hadn’t booked. Luckily, Alex spotted our booking in the ledger and pointed it out to them. We had, after all, already paid for the rooms — at great expense — via a UK banker’s draft in rupees, which was no easy feat. On the threat of violence, they agreed that we would indeed have a room. We’ll see.

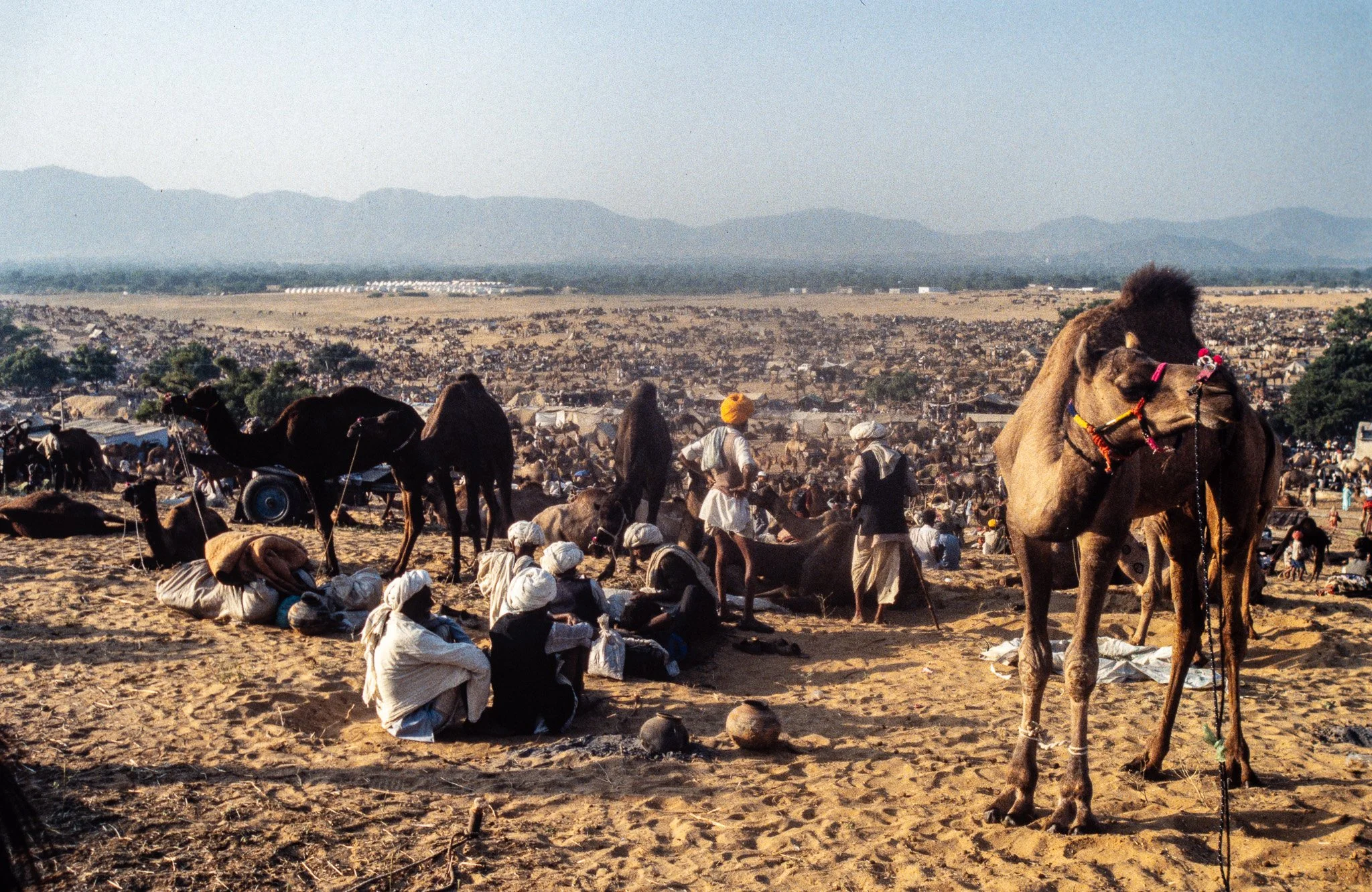

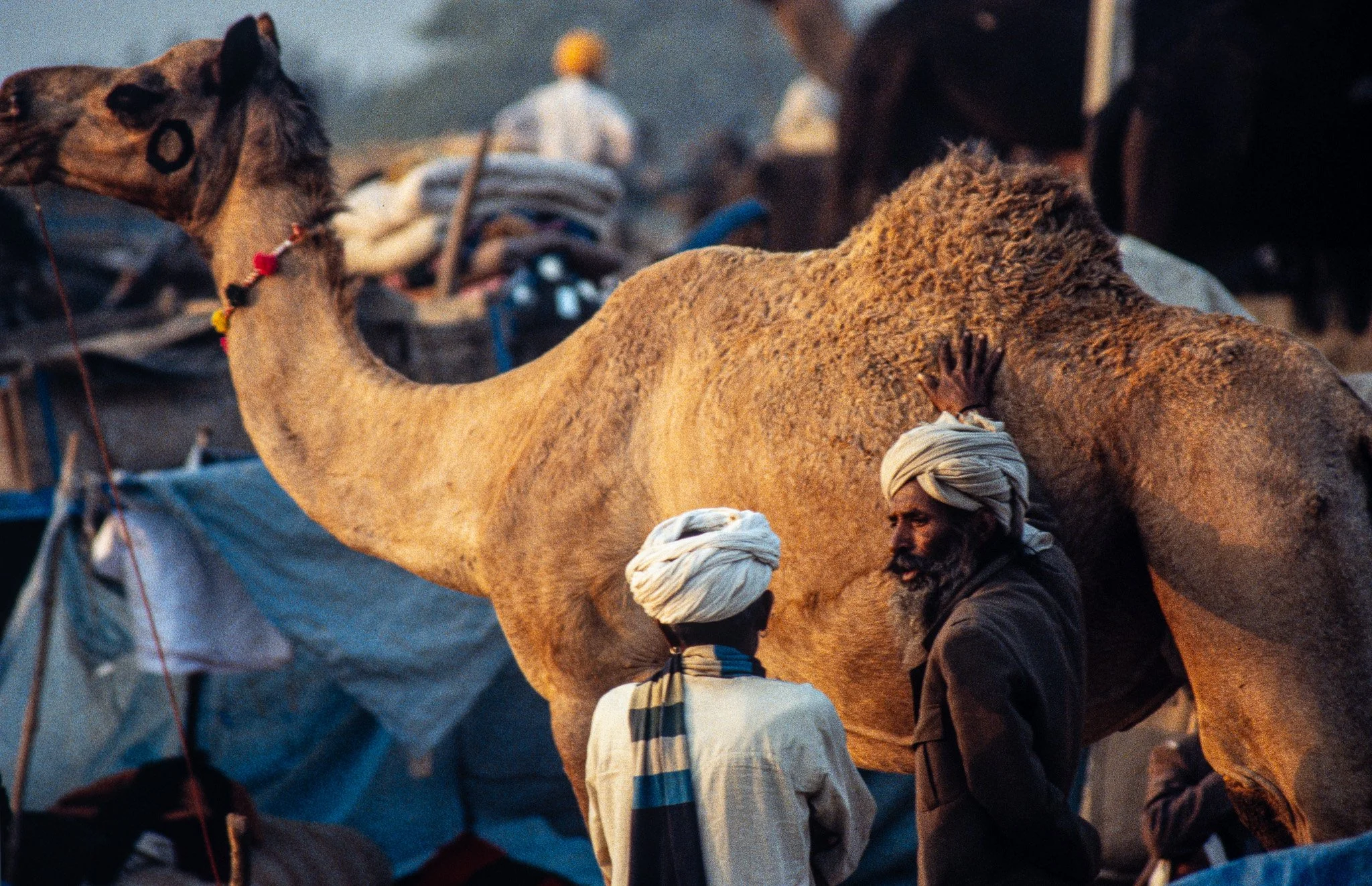

We took a local bus to Pushkar, and again people kindly moved up to give us space. The journey was relatively quick — only 11 km. We got off the bus to discover that there were no taxis or rickshaws during the camel fair. We were told this by a helpful and friendly man who showed us the route and explained a bit about the festival and the town.

I wasn’t sure why he was being so friendly without wanting to sell us something — until a few minutes later. He led us through the very attractive streets of the town, which seemed cleaner and better maintained than most, with some buildings painted in bright colours alongside the pale blue houses of the Brahmins.

It turned out that our “helper” was a Brahmin himself. He demonstrated this by showing me the holy thread under his shirt. Otherwise, he was normally dressed. He gave us each a marigold flower and said that, as we were only a minute away from the holy lake, we should throw them in for good luck.

We’d told him we were married — easier than explaining the reality — so he told us that today was the festival of Brahma, a special day for married people.